Many academics argue that an understanding of the issues around authenticity is crucial to an understanding of popular music and the dialogue that surrounds it (Atton, 1998; Frith, 1996b; Jones & Featherly, 2002; Sanjek, 1992). What is not so clear is what authenticity means in the context of popular music. All music is a performance. This holds true whether the music is being played in a live setting such as a concert hall, through an online platform like YouTube, in a recording studio, or in a bedroom on an acoustic guitar. Frith (1996b), however, argues the historical importance of the music press is ideological not commercial, and so it falls to the writers to pass judgment based on the music’s perceived authenticity and aesthetic value, not its commercial potential. Jones and Featherly are blunt: “Authenticity is critical to the discourse surrounding popular music” (2002, p. 104), as is Sanjek:

One of the central issues to rock ideology is authenticity: the degree to which a musician is able to articulate the thoughts and desires of an audience and not pander to the “mainstream” by diluting their sound or their message. (Sanjek, 1992, p. 14)

This line of thinking has dominated rock criticism since its inception in the 1960s. It includes a common denial of, or at least refusal to engage with, the fact that popular (rock) music has anything to do with commercial considerations.

‘Authentic’ rock bands are not supposed to care about sales. The reason for that is because the music critic-as-fan often uses authenticity as a tool: the band is legitimised, made authentic, by personal experience. This feeds into the fan’s sense of personal identity, and no music fan likes to believe they have been manipulated by marketing and hype. In the same way that subcultures are defined in relation to their dominant counterpart, mainstream culture, so too is the value of the players within that subculture (Thornton, 1995). Over the years, many critics and academics have interpreted that value as authenticity. Moore, for example, argues that authenticity is interpreted several different ways in relation to popular music, citing the example of Canadian singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell:

The term has frequently been used to define a style of writing or performing, particularly anything associated with the practices of the singer/ songwriter, where attributes of intimacy […] and immediacy […] tend to connote authenticity. It is used in a socio-economic sense, to refer to the social standing of the musician. It is used to determine the supposed reasons she has for working, whether her primary felt responsibility is to herself, her art, her public, or her bank balance. It is used to bestow integrity […] . (Moore, 2002, pp. 210-211)

How authenticity is defined is dependent on the subculture that is using the term. For example, “hip-hop artists claim authenticity through a form of autobiographical lyrics about racism, crime, and drug abuse, with which they establish an ethos, or ‘street cred’” (Enli, 2015, p. 12). Some form of rebellion against the dominant culture is implicit in the usage of the term in conjunction with rock music, conversant with the origins of rock in the counterculture of the 1960s.

However, that notion has changed in the last couple of decades after the assimilation of rock into mainstream culture became so apparent that it was impossible for all but the most fervent of rock fans to ignore (Grossberg, 1992). These days, to charge rock music with being more (or less) authentic than pop music lacks credibility (Kramer, 2012) and leads to charges of rockism (see above), and yet the notion persists, romanticised and mythologised by critics whose function is to romanticise and mythologise music. Authenticity is used on an ad hoc basis, applied by those so inclined with equal vigour to Top 40 chart stars and the most underground of independent artists: ‘Are they authentic to themselves as artists?’ runs a familiar nonsensical line:

Authenticity can be thought of as the compass that orients rock culture in its navigation of the mainstream. Rock fans, critics and musicians are constantly evaluating the authenticity of popular music, on the lookout for signs of alienation and inauthenticity (including, for example, over-commercialisation, insincerity, manipulation, lack of originality and so on). This preoccupation with ‘authenticity’ helps rock culture constantly to draw lines of division within the mainstream of popular music…

‘Authentic’ designates those music, musicians, and musical experiences seen to be direct and honest, uncorrupted by commerce, trendiness, derivativeness, a lack of inspiration and so on. ‘Authentic’ is a term affixed to music which offers sincere expressions of genuine feeling, original creativity, or an organic sense of community. […] authenticity is a value, a quality we ascribe to perceived relationships between music, socio-industrial practices, and listeners or audiences. (Prior, 2015, p. 131)

Within a music press (NME, Rolling Stone, Pitchfork) that favours rock and latterly ‘indie’, which is rock by any other name, authenticity is considered crucial as it is the principal point of difference between favoured bands and their ‘inauthentic’ pop counterparts. This is confirmed by Moore who writes, “The issue of what can be understood as ‘authentic’ is […] of course pertinent to the hallowed distinctions between ‘pop’ and ‘rock’” (2002, p. 210). The reason authenticity is most commonly associated with (male) rock music and inauthenticity with (female) pop music can be traced back to rock’s beginnings as an oppositional force to the dominant culture (Bangs, 1987; Grossberg, 1992) and the fact rock criticism (and, to a lesser extent, rock music itself) has up until recent times been the domain of the male.

Until the last decade and the ongoing democratisation of music criticism, few female critics have been allowed into (or wanted to be allowed into) the boys’ club of (rock) music criticism, and popular music has been shaped accordingly (Brooks, 2008; Kramer, 2012). This gender imbalance is rapidly changing however and as a result, these narrow gendered definitions of authenticity have been challenged numerous times in recent years, notably in the writing of female music critics such as Ann Powers, Maura Johnston, and Jessica Hopper, who regularly speak out against outmoded terminology. For example, Hopper contends on her blog that popular chart singer Lily Allen “regardless of what anyone thinks, is basically the Sex Pistols of girls making bedroom electronic pop” (2010), an assertion that strikes at the heart of rock ideology. In an essay reviewing Hopper’s book The First Collection of Criticism by a Living Female Rock Critic (2015) Crawford writes,

Don’t tell anyone, but I don’t own any albums by the Rolling Stones. They’re just so archetypal, so very rock and roll—and that, I find, can be a difficult thing to admire. Rock music has rarely offered women the same tangible promise of social rebellion and sexual freedom that it has given men—though plenty of women, myself included, have tried all the same to find those liberties in it. “Boy guitarists notwithstanding,” the journalist Lillian Roxon wrote to a friend, in 1966, “I don’t think I can stand the sight of another bloody electric guitar.” I know just how she felt. (2015)

On Collapse Board, a fierce debate raged during the latter half of 2011 over the concept of authenticity:

Before we go any further, let’s be clear on something. ALL music is fake. That’s why they call it a performance; that’s why they call it an act. The act of performing a song in front of people is a profoundly strange and unnatural thing. It is ALWAYS pretentious. There is ALWAYS some degree of artificiality to it. People don’t normally get up in front of a bunch of strangers and express themselves melodically. It is, whether the artist is aware of it or not, an act of creation that—while it may share some, or no, similarities with the artist—is not the same thing as the person doing the creating. (Creney, 2011)

Being deemed authentic is one of the lines used by both critics and academics to separate high (or middle) brow contemporary music from lowbrow (mass-produced) pop. However, in the increasingly complex and complicated world of web 2.0 environments, this idea is becoming less and less relevant as it becomes easier to fake authenticity. Every heard song has been mediated by the production process and other related processes, whether in a live setting or in a studio. Every song reflects the character of the personality and identity of the persons performing it, the same way all fiction is rooted at some level in ‘fact’ and all factual writing is rooted to some degree in ‘fiction’. As pioneer filmmaker Jim Jarmusch puts it (while conflating use of the word ‘authenticity’):

Nothing is original. Steal from anywhere that resonates with inspiration or fuels your imagination. Devour old films, new films, music, books, paintings, photographs, poems, dreams, random conversations, architecture, bridges, street signs, trees, clouds, bodies of water, light and shadows. Select only things to steal from that speak directly to your soul. If you do this, your work (and your theft) will be authentic. Authenticity is invaluable: originality is non-existent. And don’t bother concealing your thievery—celebrate it if you feel like it. In any case, always remember what Jean-Luc Godard said: “It’s not where you take things from—it’s where you take them to”. (2010)

Not all academics believe that authenticity is a useful classificatory tool. Many argue that authenticity does not exist within popular music, or if it does, it exists at such a low level within every performer as to have little or no value as a descriptive tool (Williams, 2006). And yet the notion of authenticity in popular music persists, constructed via various conventions and tricks, as Enli (2015, p.136) terms them in relation to media studies; predictability, spontaneity, immediacy, confessions, ordinariness, ambivalence and imperfection.

Enli argues that the “paradox of mediated authenticity is that although we base most of our knowledge about society and the world in which we love on mediated representations of reality, we remain well aware that the media are constructed, manipulated, and even faked” (p. 1). That paradox is central to an understanding of the ideology of rock (and thus popular music) criticism. Popular music is a mediated representation of reality, constructed and manipulated, and yet rock fans are frequently searching for what they believe to be an unmediated representation of the bands they give their support to.

Weisethaunet and Lindberg (2010) reason that the concept of authenticity when applied to popular music is even vaguer than when it is used in philosophy, where it has already become so vague as to become near-meaningless (p. 481). To illustrate their argument, the pair break down the concept in detail, and give examples of differing forms of authenticity that occur within different forms of popular music: “Folkloric ‘Authenticity’”, “‘Authenticity’ as Self-Expression”, “‘Authenticity’ as Negation”, “‘Authentic Inauthenticity’”, “Body ‘Authenticity’”, and so on (pp. 469-476). This should serve as a good example of the definitional confusion that awaits any academic or critic attempting to justify usage of the term. Establishing what authenticity actually means is highly problematic. A more sound approach is to use ‘the illusion of authenticity’. As Frith points out,

Critical judgement means measuring performers’ ‘truth’ to the experience or feelings they are describing or expressing. The problem is that it is, in practice, very difficult to say who or what it is that pop music expresses or how we recognize, independently of their music, the ‘authentically’ creative performers. Musical ‘truth’ is precisely that which is created by ‘good music’; we hear the music as authentic (or rather, we describe the musical experience we value in terms of authenticity) and such a response is then read back, spuriously, on to the music-making (or listening) process. (1996a, p.121)

Frith argues that the question is framed incorrectly: it should not be “what does popular music reveal about the people who play and use it”? Rather, it should be “how does popular music create them as people, as a web of identities?” (p. 121). All art is performance, or, as Creney (2011) bluntly terms it, “ALL music is fake”—and so the idea of looking to it to discover the ‘real’ person that lurks behind the façade lacks credibility:

Popular music is popular not because it reflects something or authentically articulates some sort of popular taste or experience, but because it creates our understanding of what ‘popularity’ is, because it places us in the social world in a particular way. What we should be examining […] is not how true a piece of music is to something else, but how it sets up the idea of ‘truth’ in the first place. (Frith, 1996a, p. 121)

I propose that until an understanding of the importance of the illusion of authenticity to rock criticism is reached, understanding various motivations and patterns of popular music criticism will remain problematic because the roots of what is termed popular music criticism in the present-day are so closely aligned with the roots of rock criticism. If popular music criticism is to lose the ‘death of the music critic’ tag and adapt to changing taste patterns in web 2.0 environments it needs to acknowledge the role the illusion of authenticity played in its creation, and still plays in much of present-day writing around music.

From The Slow Death of Everett True: A Metacriticism (Thackray, 2016, pp. 74-79)

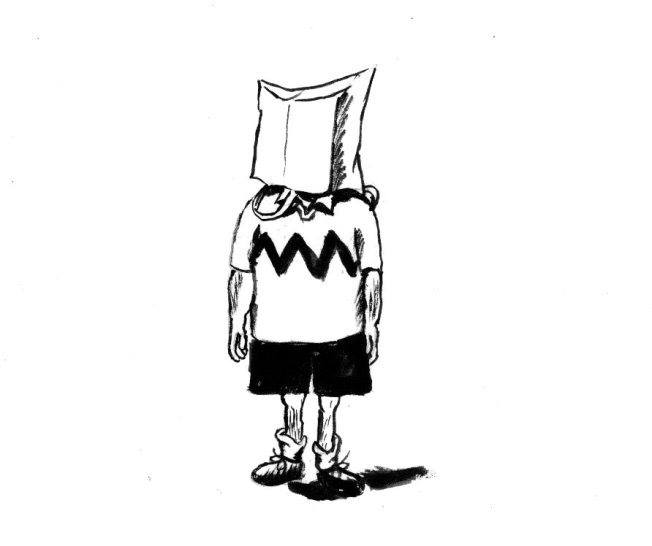

Illustration: Vincent Vanoli

What an interesting, informative read. When I think of authenticity in rock, the first thing that comes to mind is the lo-fi-by-necessity production of garage bands, where urgency and ambition seem to take priority over skill and fumbles wind up part of the finished product. To me, that’s where the romance of authenticity comes in, and I do associate it most strongly with rock, but I suppose it’s really more about stage of music making than genre.